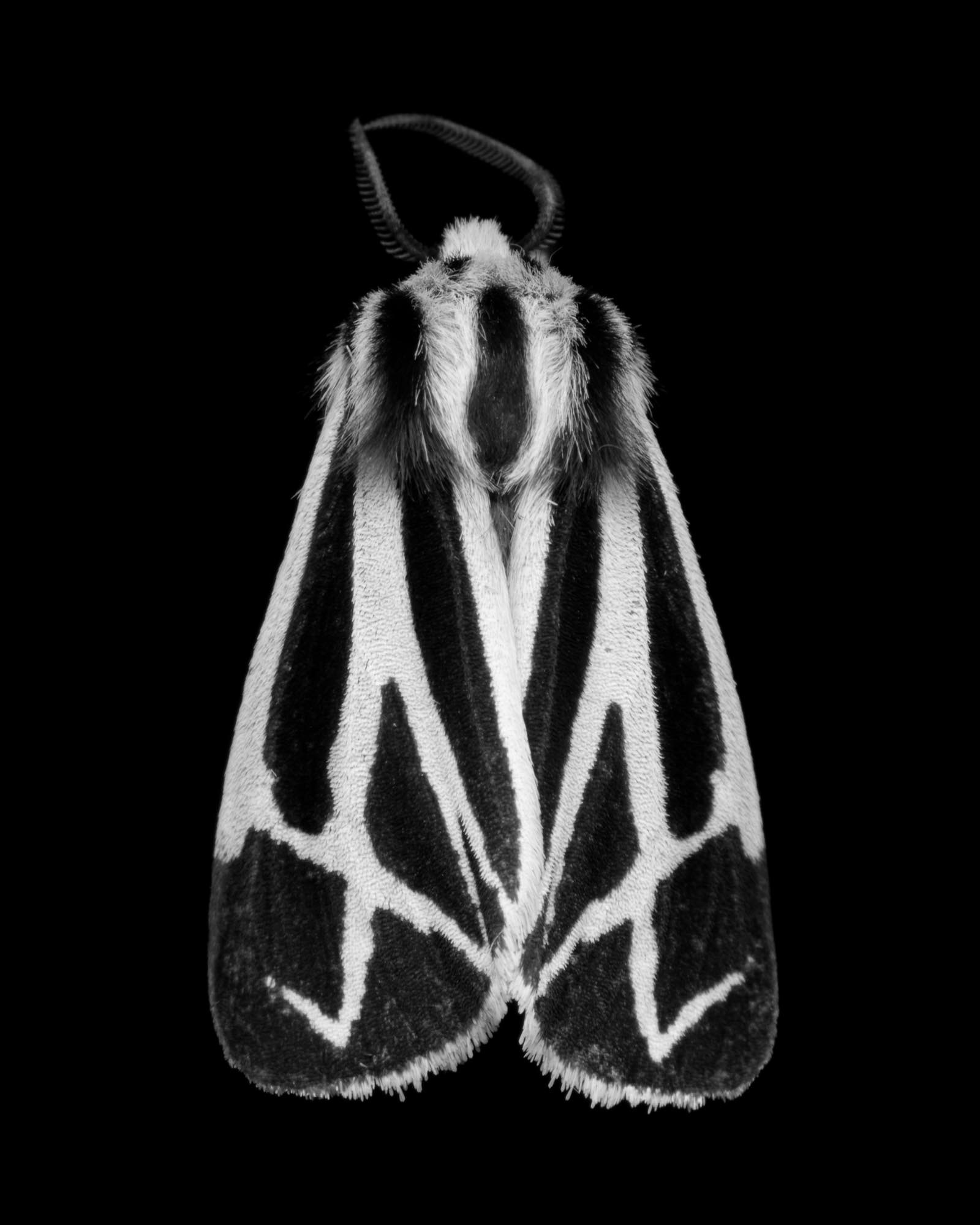

Antheraea polyphemus (polyphemus moth), 19th century, 2007, ambrotype, 7.25x7.25"

Antheraea polyphemus (polyphemus moth), 21st century, 2007, archival pigment print, 40x40"

Odonata epiprocta (dragonfly), 19th century, 2007, ambrotype, 7.25x7.25"

Odonata epiprocta (dragonfly), 21st century, 2008, archival pigment print, 40x40"

Actias Luna I (luna moth) 19th century, 2008, ambrotype, 7.25x7.25"

Actias Luna I (luna moth) 21st century, 2008, archival pigment print, 40x40"

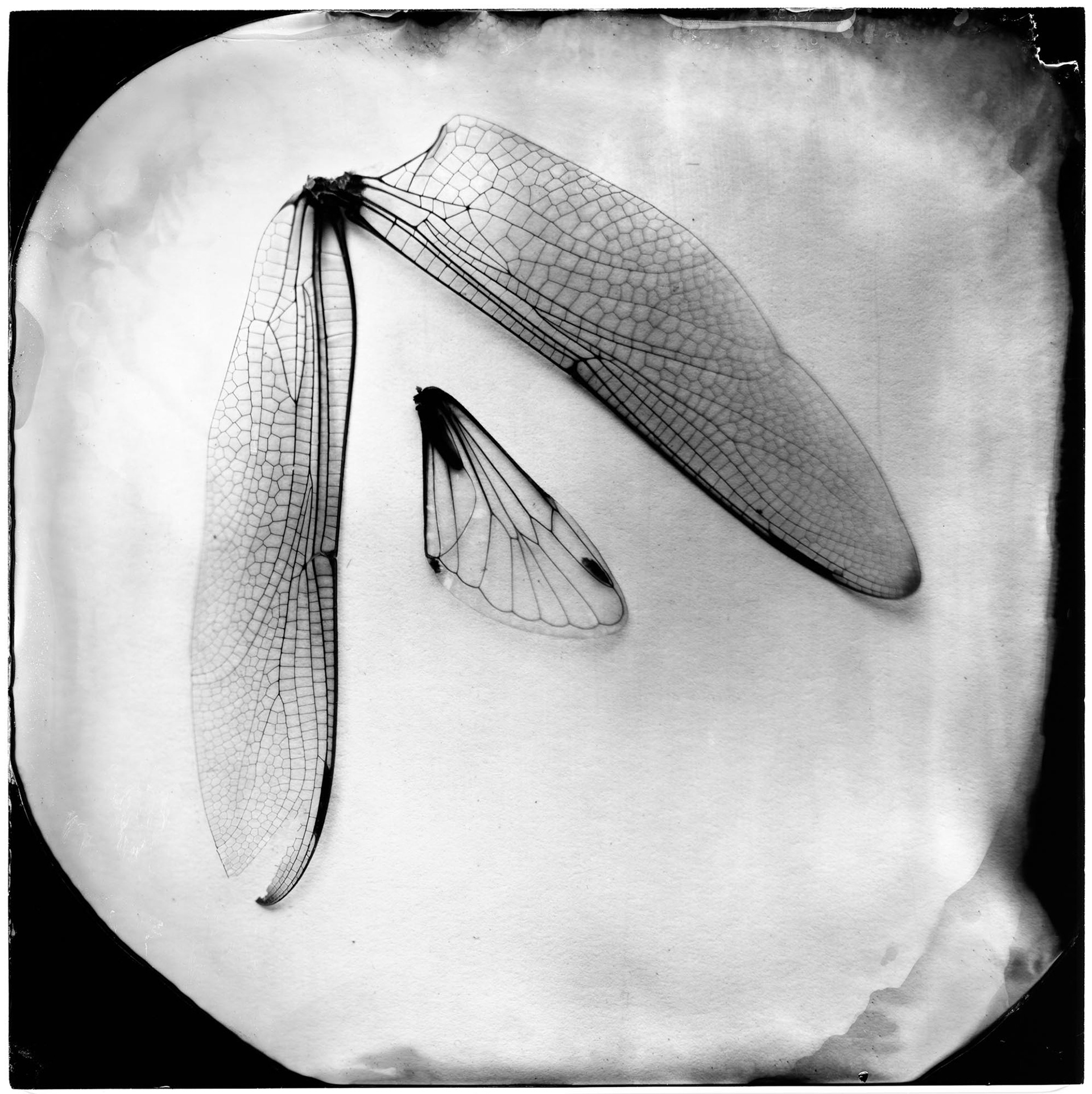

Dragonfly and Cicada Wings, 19th century, 2008, ambrotype, 7.25x7.25"

Dragonfly and Cicada Wings, 21st century, 2008, archival pigment print, 40x40"

Actias Luna II (luna moth) 19th century, 2008, ambrotype, 7.25x7.25"

Actias Luna I (luna moth) 21st century, 2008, archival pigment print, 40x40"

Moth Wings (female luna, male polyphemus), 19th century, 2008, ambrotype, 7.25x7.25"

Moth Wings (female luna, male polyphemus), 21st century, 2008, archival pigment print, 40x40"